Table of Contents

ToggleOSI and TCP/IP Models.

OSI Model (7 Layers)

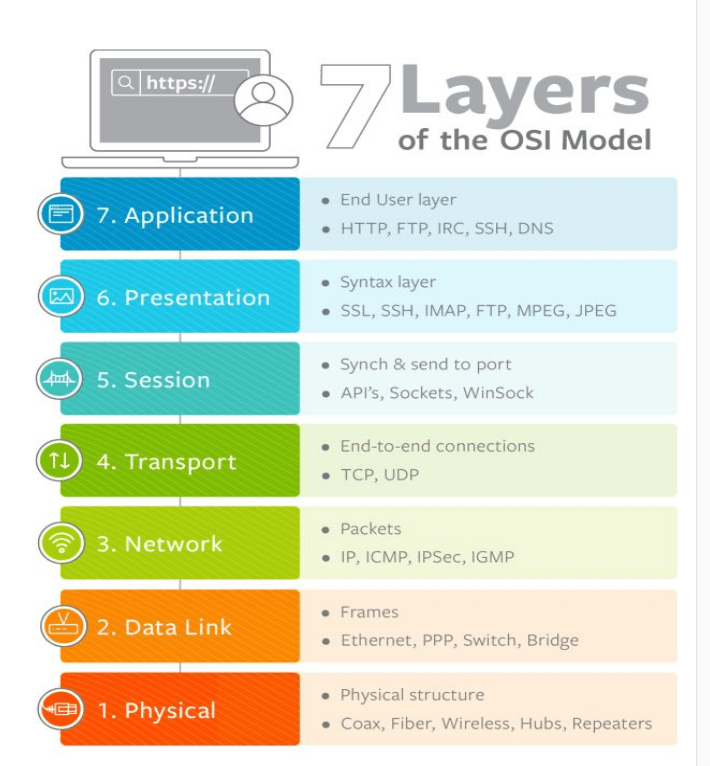

The OSI model, or Open Systems Interconnection model, is a conceptual framework that standardizes the functions of a telecommunication or computing system without regard to its underlying internal structure. It divides the communication process into seven distinct layers, each with specific responsibilities, allowing diverse systems to communicate efficiently. The first layer is the Physical Layer, which deals with the transmission of raw bits over a physical medium such as cables, fiber optics, or wireless channels. It defines hardware specifications, signal types, data rates, and physical connectors. Next comes the Data Link Layer, responsible for node-to-node data transfer, error detection, and correction. It packages raw bits into frames and ensures reliable communication between devices on the same network. Protocols like Ethernet and MAC addressing operate at this layer. The third layer, the Network Layer, handles logical addressing, routing, and path determination. It ensures that data packets move from the source device to the correct destination across multiple networks, using IP addresses and routers. Layer four is the Transport Layer, which manages end-to-end communication, flow control, and error recovery. It ensures complete and accurate delivery of messages, with protocols such as TCP and UDP providing reliability or speed, depending on application requirements.

The fifth layer, the Session Layer, establishes, manages, and terminates communication sessions between applications. It coordinates dialog control, synchronization, and data exchange checkpoints to ensure smooth interactions between systems. Above this, the Presentation Layer is responsible for data translation, encryption, and compression. It converts data into a format that the application layer can understand, ensuring interoperability between different data representations and secure transmission when necessary. Finally, the Application Layer is the topmost layer, where user interaction occurs. It provides network services directly to applications, including email, file transfer, web browsing, and remote access, using protocols like HTTP, FTP, and SMTP. Each layer in the OSI model communicates with its adjacent layers through well-defined interfaces, allowing modular design and easier troubleshooting. The OSI model also promotes interoperability between different vendors’ hardware and software, providing a universal language for networking. By isolating network functions, it simplifies development, maintenance, and understanding of complex systems.

The layered approach ensures that changes in one layer, such as upgrading hardware at the Physical Layer, do not affect other layers. Network engineers, developers, and IT professionals use the OSI model as a guideline for designing protocols, diagnosing network problems, and understanding network behavior. Understanding each layer’s function is crucial for efficient network design, security implementation, and performance optimization. The OSI model is theoretical but widely applied as a reference model for network communication. Despite the rise of the TCP/IP model, which merges some OSI layers, the OSI model remains an essential educational tool and a foundation for understanding modern networking. Its structured approach allows clear separation of concerns, reduces complexity, and enhances scalability in global networks. The OSI model also provides a roadmap for troubleshooting: by isolating issues layer by layer, network professionals can quickly identify and resolve faults. The model emphasizes standardization, interoperability, and flexibility, which are vital for the heterogeneous nature of today’s networks. Overall, the OSI model is a timeless framework that guides the design, implementation, and maintenance of reliable and efficient network communication systems. It remains a cornerstone in networking education and professional practice, bridging theoretical knowledge with practical application. By following its seven layers, networks achieve modularity, robustness, and systematic organization, ensuring seamless connectivity across diverse computing environments.

1. Physical Layer – Deals with physical transmission (e.g., cables, radio waves).

The Physical Layer is the first and lowest layer of the OSI model, and it plays a fundamental role in networking by dealing with the actual physical transmission of data between devices. It is responsible for converting raw bits into electrical, optical, or radio signals that can travel across a communication medium, whether it is copper cables, fiber-optic cables, or wireless channels.

This layer defines the mechanical and electrical specifications of the network hardware, including connectors, voltage levels, timing of signals, and the physical layout of cables and devices. The Physical Layer also establishes the data rate, which is the speed at which data is transmitted over the medium, and it determines how many bits per second can be sent without error. Signal modulation and encoding are handled here, ensuring that data can be transmitted efficiently and accurately over various types of transmission media. For example, in wired networks, the Physical Layer specifies the use of twisted-pair cables, coaxial cables, or fiber optics, while in wireless networks, it defines radio frequencies, transmission power, and antenna characteristics. Devices such as network interface cards (NICs), hubs, repeaters, and transceivers operate at this layer to facilitate the physical connection between systems.

It also manages synchronization of bits, meaning it ensures that the sender and receiver are aligned in terms of timing to interpret the binary signals correctly. Physical topologies, such as bus, star, ring, or mesh, are part of this layer, describing how devices are physically connected in a network. The Physical Layer does not concern itself with the meaning of the data being transmitted; it simply moves raw bits from one device to another. This layer also addresses issues like signal attenuation, which is the weakening of a signal over distance, and noise, which can interfere with transmission.

Repeaters are used to amplify or regenerate signals to overcome attenuation in long-distance communication. Crosstalk, electromagnetic interference, and other environmental factors are considered at this layer to maintain signal integrity. Standards such as IEEE 802.3 for Ethernet, IEEE 802.11 for Wi-Fi, and ITU-T recommendations define the Physical Layer specifications for different network technologies. In addition, the Physical Layer is crucial in determining bandwidth, which is the range of frequencies that a medium can carry, affecting the overall speed and capacity of the network.

Cable length limitations, connector types, and pin configurations are also defined by this layer to ensure compatibility and performance. The layer also deals with duplexing methods, specifying whether communication is half-duplex or full-duplex, impacting how data flows between devices. Clocking and timing mechanisms are vital here, as they control the pace at which bits are sent and ensure synchronization between sender and receiver. The Physical Layer serves as the foundation for all other layers in the OSI model, as proper physical transmission is necessary for data link protocols, routing, and higher-level communications. Errors at this layer, such as damaged cables or signal degradation, can disrupt the entire communication process, making troubleshooting at the Physical Layer essential.

Modern networking technologies, including fiber optics and high-speed wireless standards, push the capabilities of the Physical Layer, allowing for faster and more reliable transmission over longer distances. Electrical characteristics, like voltage swings and impedance, are carefully specified to avoid reflection and signal loss. The layer also includes standards for connectors, such as RJ-45 for Ethernet and SC or LC for fiber optics, to ensure universal interoperability.

The Physical Layer is the starting point for establishing network connectivity, providing the necessary infrastructure for transmitting data in the form of binary signals. It acts as a bridge between the abstract digital information used by computers and the tangible physical medium through which that information travels. Power over Ethernet (PoE) is an example of a modern feature implemented at this layer, allowing electrical power to be transmitted along with data.

Overall, the Physical Layer is critical for the reliable and efficient movement of data, as all higher layers depend on its proper functioning to communicate effectively. Without a well-defined Physical Layer, network communication would fail, as signals could not be transmitted, received, or interpreted correctly by devices. It ensures that bits are physically transmitted across the network, laying the foundation for all higher-level protocols and services. By defining the hardware, signaling, and media requirements, the Physical Layer enables the network to operate smoothly, forming the backbone of the entire OSI model and making modern digital communication possible.

2. Data Link Layer – Handles MAC addressing and error detection.

The Data Link Layer is the second layer of the OSI model, and it is primarily responsible for providing reliable node-to-node communication over a physical link. It ensures that data transferred from the Physical Layer is free from errors and properly synchronized between devices on the same network. This layer takes raw bits from the Physical Layer and organizes them into frames, which include not only the data but also control information, such as source and destination addresses, error detection codes, and sequencing information. One of its key functions is MAC addressing Media Access Control addresses uniquely identify devices on a local network, allowing proper delivery of frames.

The Data Link Layer also implements error detection and correction, typically using techniques like cyclic redundancy check (CRC) to detect corrupted frames and request retransmission. It manages flow control, ensuring that a fast sender does not overwhelm a slower receiver, and handles access to the shared physical medium in networks where multiple devices compete to transmit data. This layer is divided into two sublayers: the Logical Link Control (LLC) sublayer, which handles error checking and flow control, and the Media Access Control (MAC) sublayer, which governs how devices access the physical medium.

Common protocols operating at this layer include Ethernet, Wi-Fi (IEEE 802.11), and PPP (Point-to-Point Protocol). The Data Link Layer also defines physical addressing methods and rules for how devices communicate within the same local area network (LAN) or across point-to-point links. Switches operate primarily at this layer, forwarding frames based on MAC addresses and reducing network collisions. It also plays a role in error isolation, so that problems in one segment do not affect the entire network. By detecting errors and retransmitting frames when necessary, the Data Link Layer ensures reliable communication over imperfect physical channels. In addition, it supports frame sequencing, which preserves the correct order of data packets during transmission.

Overall, the Data Link Layer acts as a bridge between the raw transmission of the Physical Layer and the routing and addressing functions of the Network Layer. It provides a structured, reliable, and error-free method to transmit data, ensuring that devices on the same network can communicate efficiently and accurately. Without the Data Link Layer, networks would be prone to collisions, data corruption, and misdelivery, making higher-level communication unreliable. It ensures proper addressing, reliable delivery, and error handling, forming a crucial part of the OSI model’s layered architecture.

3. Network Layer – Manages IP addressing and routing.

The Network Layer is the third layer of the OSI model, and its primary function is to manage logical addressing and routing so that data can travel from the source device to the destination device across multiple networks. Unlike the Data Link Layer, which operates within a single network segment, the Network Layer handles end-to-end delivery of packets across different networks, ensuring that information reaches the correct destination even if the source and destination are separated by routers, switches, or other intermediate devices.

One of the key components of this layer is IP addressing, which provides a unique identifier for each device on a network. This logical addressing allows the Network Layer to determine the source and destination of each packet independently of the underlying physical network. Routing is another critical function, where the Network Layer uses routing algorithms and protocols to determine the most efficient path for data to travel. Devices such as routers operate at this layer, reading packet headers to forward data to the next hop on its journey toward the destination.

Common protocols at the Network Layer include the Internet Protocol (IP), ICMP, and IPsec, which help with addressing, error messaging, and security. The layer also handles packet fragmentation and reassembly, breaking down large packets into smaller fragments for transmission over networks with size limitations and then reassembling them at the receiving end. In addition, the Network Layer ensures congestion control and traffic management, deciding how packets are prioritized when networks become busy to optimize performance and reduce delays. It provides logical separation of networks through subnets, allowing network administrators to organize devices efficiently and improve security.

Address resolution protocols, such as ARP, help map logical addresses to physical MAC addresses when packets move from the Network Layer to the Data Link Layer for actual transmission. The Network Layer also supports error reporting and diagnostics, providing information about unreachable destinations or network failures, which is crucial for troubleshooting and maintaining reliability. Advanced features include support for virtual private networks (VPNs) and tunneling, which allow secure communication across public networks. It is responsible for maintaining end-to-end connectivity, independent of the hardware used in the underlying networks, providing a seamless experience for higher-layer applications. The layer must account for different network topologies, whether star, mesh, or hybrid, ensuring packets are delivered efficiently despite complex network layouts.

Protocols like OSPF, BGP, and RIP operate at this layer to manage routing tables and ensure optimal paths are chosen dynamically. The Network Layer also supports quality of service (QoS), allowing critical traffic to be prioritized over less important data, which is essential for applications like VoIP or streaming. Addressing schemes such as IPv4 and IPv6 provide unique identifiers for devices and help route traffic in both local and global networks. By managing logical addresses, packet forwarding, and routing decisions, the Network Layer ensures that data can traverse heterogeneous networks, linking LANs, WANs, and the Internet seamlessly. Security measures such as IP filtering and firewalls operate at this layer to prevent unauthorized access and attacks.

Overall, the Network Layer serves as the backbone of inter-network communication, connecting devices across vast distances and different technologies. Its proper functioning is essential for ensuring reliable, efficient, and accurate delivery of data packets, supporting all higher-level operations in the OSI model. By abstracting the underlying hardware and focusing on logical addressing and routing, the Network Layer enables scalable, robust, and manageable network communication, forming a critical bridge between local data transmission and global network connectivity.

4. Transport Layer – Ensures reliable communication using TCP/UDP.

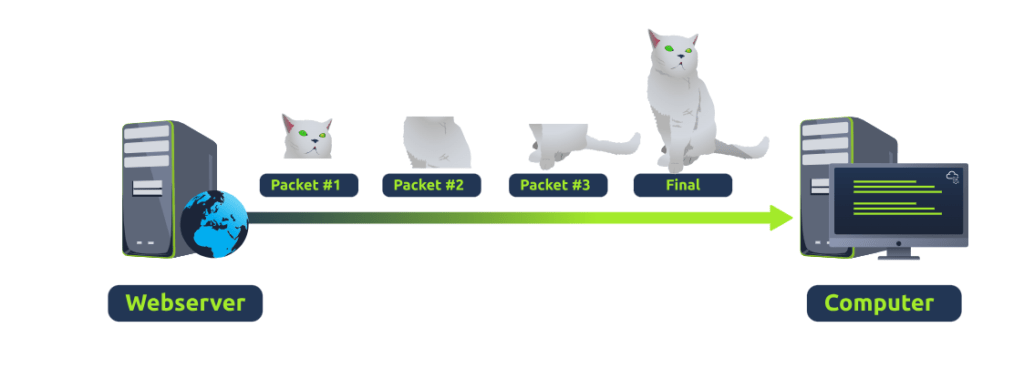

The Transport Layer is the fourth layer of the OSI model, and it is responsible for providing end-to-end communication between devices and ensuring that data is delivered accurately and reliably. This layer takes data from the upper layers, divides it into smaller segments, and manages the transmission of these segments across the network, ensuring that they are reassembled correctly at the destination.

One of the main responsibilities of the Transport Layer is error detection and correction, which ensures that lost or corrupted data is retransmitted, providing reliability for critical communications. Protocols like TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) offer reliable, connection-oriented communication by establishing a session, sequencing segments, and acknowledging receipt of data. In contrast, UDP (User Datagram Protocol) provides connectionless, fast transmission without guaranteeing delivery, making it suitable for real-time applications such as video streaming, gaming, or VoIP. The Transport Layer also manages flow control, ensuring that a fast sender does not overwhelm a slower receiver, and congestion control, preventing network overload. Each segment includes a header with information such as source and destination port numbers, allowing multiple applications on the same device to communicate simultaneously.

This layer acts as a bridge between the reliable delivery of data and the services provided by the Session, Presentation, and Application layers above it. By providing segmentation, error checking, and traffic management, the Transport Layer ensures that applications can communicate effectively, regardless of network conditions. It also provides multiplexing, allowing multiple communication streams to coexist without interference, which is essential for modern multitasking environments.

The Transport Layer ensures the integrity, sequencing, and completeness of data, forming a critical foundation for applications like web browsing, file transfer, email, and online gaming. Without this layer, higher-level services would face data loss, misordering, or duplication, leading to unreliable and inconsistent communication. Overall, the Transport Layer is essential for providing a reliable, organized, and efficient means of moving data between devices across diverse and complex networks, supporting both speed and accuracy as needed.

5. Session Layer – Maintains communication sessions.

The Session Layer is the fifth layer of the OSI model, responsible for establishing, managing, and terminating communication sessions between applications on different devices. It acts as a coordinator, ensuring that data exchange occurs in an organized and synchronized manner. This layer sets up connections between applications, manages dialog control, and keeps track of which side is sending and receiving data.

It supports full-duplex, half-duplex, or simplex communication, allowing the session to match the requirements of the applications. The Session Layer also provides checkpointing and recovery, which allows long-running transmissions to resume from the last checkpoint if an interruption occurs, rather than starting over. Protocols such as RPC (Remote Procedure Call) and NetBIOS operate at this layer to facilitate session management. By handling the opening, closing, and synchronization of sessions, this layer ensures that communication is orderly and that multiple simultaneous conversations do not interfere with each other.

The Session Layer also coordinates security and authentication, verifying that the session is established between authorized entities. It provides a stable environment for the Presentation and Application layers to communicate effectively, allowing applications to exchange data without worrying about the underlying network disruptions. Overall, the Session Layer plays a crucial role in maintaining structured, reliable, and organized communication, enabling higher-level applications to function smoothly over complex networks.

6. Presentation Layer – Converts data formats (e.g., encryption).

The Presentation Layer is the sixth layer of the OSI model, and its main responsibility is to translate, format, and prepare data so that it can be understood by the Application Layer. It acts as a translator between different data formats, ensuring that data sent from one system can be correctly interpreted by another, regardless of differences in encoding, character sets, or data representation. This layer handles data conversion, such as converting between ASCII, EBCDIC, or Unicode formats, and ensures consistent interpretation of numbers, text, images, or other complex data types.

The Presentation Layer also provides data compression, reducing the size of transmitted data to improve network efficiency and speed. Additionally, it implements encryption and decryption, ensuring that sensitive information is securely transmitted across the network, protecting it from unauthorized access. Protocols like SSL/TLS operate at this layer to provide secure communication for web browsing, email, and other applications. By handling syntax and semantics of data, the Presentation Layer ensures that the Application Layer can interact with data without worrying about underlying encoding or security mechanisms.

It also manages serialization and deserialization, converting complex data structures into a transmittable format and reconstructing them at the receiving end. This layer essentially bridges the gap between the raw data transmission handled by lower layers and the meaningful application-level processes, providing a consistent and secure interface for applications. Overall, the Presentation Layer ensures that data is properly formatted, encoded, compressed, and encrypted, allowing seamless and secure communication between heterogeneous systems across the network.

7. Application Layer – Provides network services to users (e.g., HTTP, FTP).

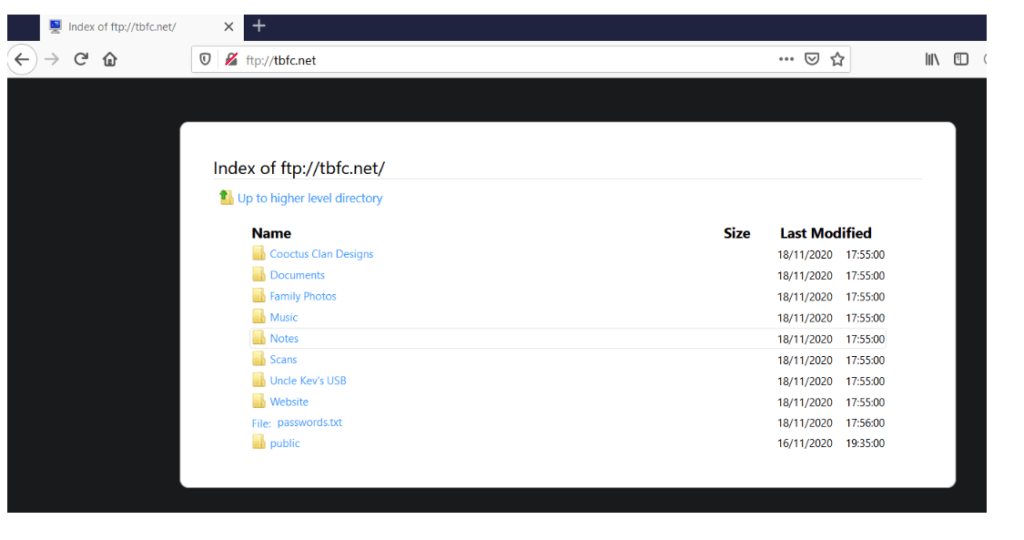

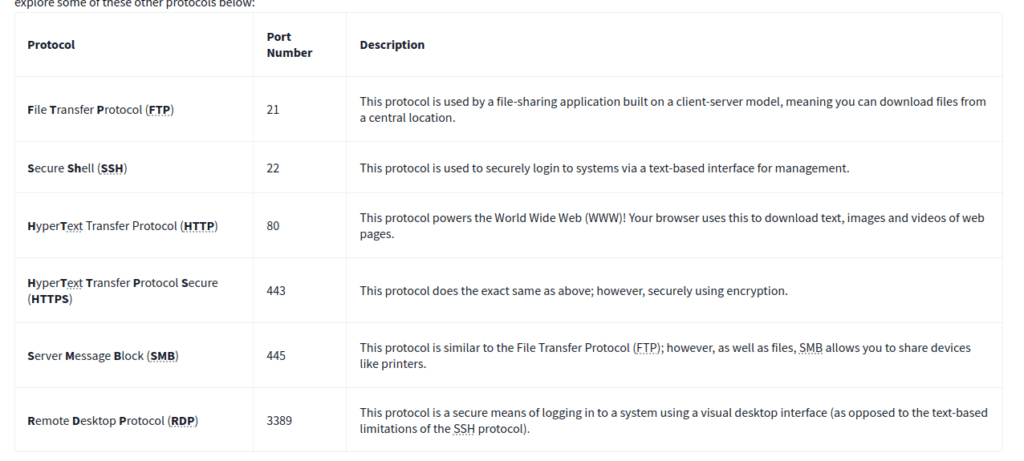

The Application Layer is the seventh and topmost layer of the OSI model, responsible for providing network services directly to end-users and applications. Unlike the lower layers, it does not handle data transport or routing; instead, it interacts with software applications to enable communication over the network. This layer provides protocols and services such as HTTP for web browsing, FTP for file transfer, SMTP for email, and DNS for domain name resolution, allowing users to perform tasks without worrying about the underlying network operations.

It also supports network-based applications like instant messaging, video conferencing, and cloud services, ensuring that data from these applications can be properly transmitted and received. The Application Layer manages user authentication, permissions, and access to resources, ensuring that only authorized users can interact with services. It also provides a platform for higher-level functionalities such as file sharing, remote login, and database access, bridging the gap between end-user programs and the lower OSI layers. Error handling and session initiation may also be partially facilitated here, in coordination with the Presentation and Session layers.

By providing a standard interface, the Application Layer enables interoperability between different systems and software, making network communication accessible and practical for everyday users. It is the layer closest to the end-user, translating their requests into network actions while presenting the results in a readable or usable format. Overall, the Application Layer plays a crucial role in ensuring that network services are efficient, accessible, and user-friendly, acting as the gateway through which users interact with the network and enabling all higher-level communication activities to function smoothly and reliably.

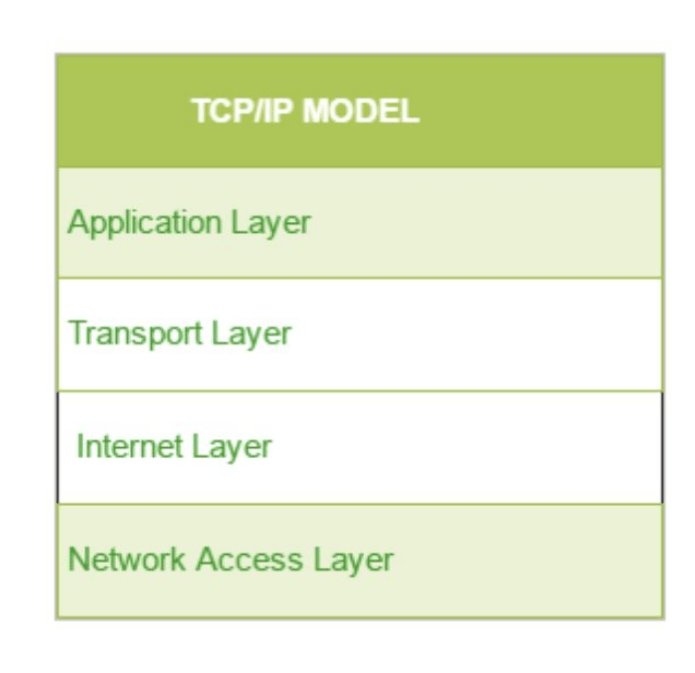

TCP/IP Model (4 Layers)

1. Network Access Layer – Combines OSI’s Physical & Data Link layers.

2. Internet Layer – Equivalent to OSI’s Network Layer (IP addressing & routing).

3. Transport Layer – Uses TCP (reliable) or UDP (fast but unreliable).

4.Application Layer – Includes HTTP, FTP, SMTP, etc.

Conclusion.

In conclusion, a strong understanding of basic networking concepts is essential for DevOps engineers, as modern software deployment, infrastructure automation, and cloud operations all rely heavily on network communication. Knowledge of IP addressing, subnetting, routing, DNS, firewalls, and protocols like HTTP, TCP, and UDP enables DevOps professionals to design scalable, secure, and efficient systems. Networking concepts also play a critical role in monitoring, troubleshooting, and optimizing application performance, ensuring that services remain reliable and available. By mastering these fundamentals, DevOps engineers can bridge the gap between development and operations, streamline deployment pipelines, manage containers and microservices effectively, and implement resilient infrastructure on cloud platforms. Ultimately, networking knowledge empowers DevOps engineers to create robust, fault-tolerant environments, facilitate seamless communication between services, and support continuous integration and delivery practices, making it a cornerstone of modern DevOps proficiency.